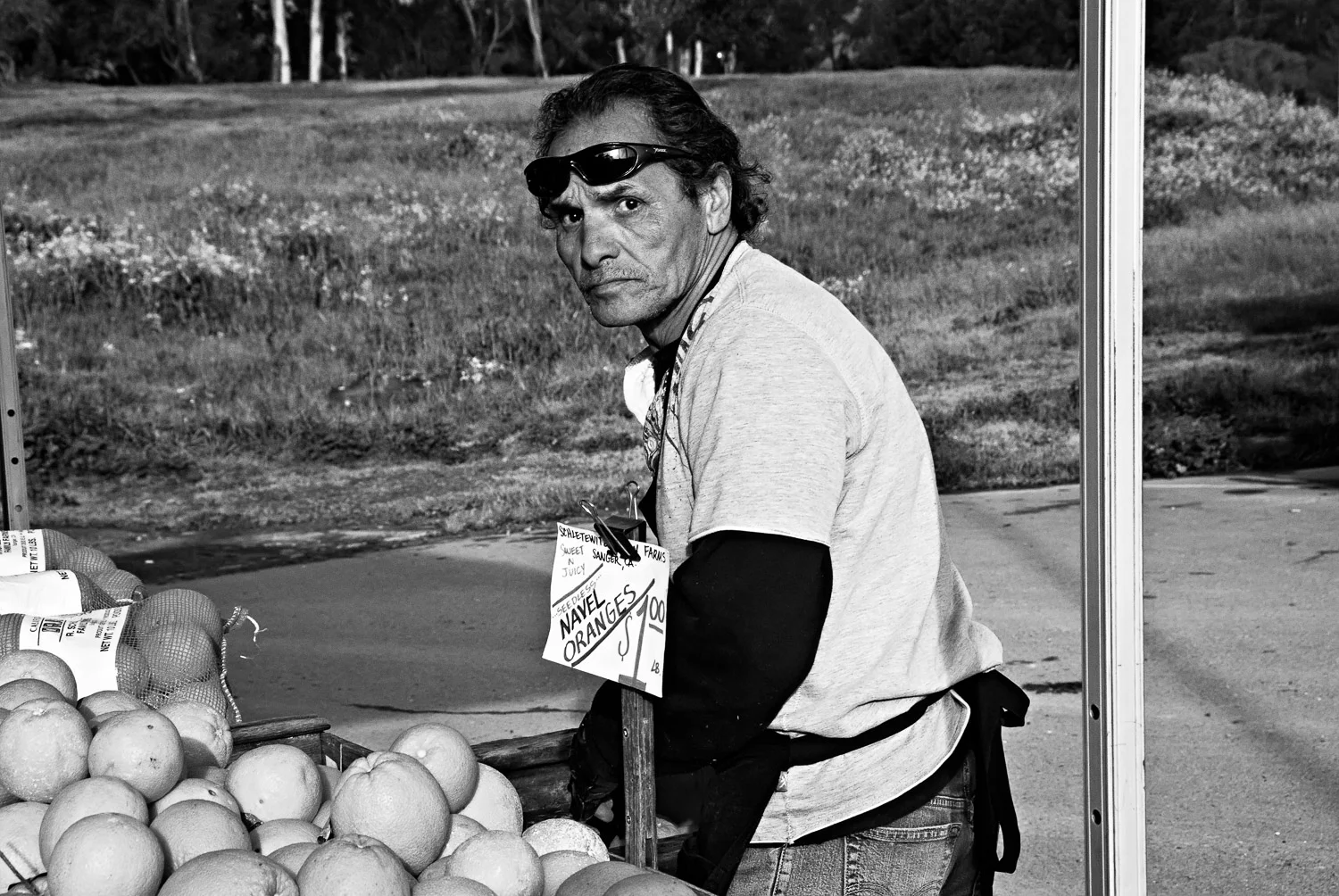

Worker, Farmer's Market | Mark Lindsay

I saw three big cameras at the farmer's market this weekend. They seemed to transform the photographers into something imposing and separate from the life of the market. Lenses are getting longer and bulkier. It used to be that a zoom lens was an extravagance—it was most certainly a tradeoff in quality. Back in my youth, most serious photographers used prime lenses because zooms were so unsharp. Now everyone seems to use a zoom lens. I do, though with ambivalence.

While zoom lenses are enormously helpful, they do tend to keep us away from our subjects. It's so much easier to zoom in than it is to move in. But, moving in is where the action is. Moving in takes interaction and courage. There is nothing worse than a portfolio of people images, all photographed with a long-focal-length lens. The detachment and sterility are palpable.

Move in. I remind myself of this constantly. Sometimes I do, other times I succumb to the shyness and laziness of staying back letting the lens to the work. Moving in forces an interaction between camera and subject. The camera becomes part of the stage, the unseen actor that provokes reaction.

One of the best-known encounters with camera is exhibited in the famous photo of Joseph Goebbels by Alfred Eisenstaedt. Shot in Geneva in 1933, Goebbels glares at Eisenstaedt as the photographer moves in with his camera. It is chilling preview of Nazi horrors to come. Eisenstaedt, a Jew, courageously intruded into Goebbels personal space to evoke the hidden veracity of the Nazi regime. A long lens would have yielded nothing more than a tabloid-style throw-away image. Instead, we see truth.

This weekend at the market I tried to move in whenever possible. The result is today's image of one of the market workers as he looked up at me for a spit second. For that moment we saw each other, interacted, and acknowledged each other's existence. I don't think it's a deep photo, but it does have power—thanks to moving in.