Looking at Daguerre | Mark Lindsay

Photography is magic. I suppose we all know that but it's become so common and easy that we have become desensitized to the miracle of it. I do love the way most everyone plays with photography now. I see people making images everywhere I go, with phones, automated cameras, and gadgets of all kinds. Yet, digital imaging is so immediate and so very automated that I wonder if some of the magic and wonder have been bred out of photography.

I've been feeling it within myself. With digital imaging, I now make more images than ever. It's not uncommon to come home from an outing with 500 photos on my memory cards. My database of images is now so large that I've forgotten many of the pictures—they get lost in the virtual stack. I can't get my mind around it.

I've been sensing the need to reconnect with the history of photography and the deliberate nature of traditional processes. So, I took a class in the making of daguerreotypes this past weekend. Given by Michael Shindler at the RayKo Photo Center in San Francisco, and sponsored by SFMOMA's Foto Forum, it was one of the most remarkable experiences I've ever had. Michael, a gifted and extraordinarily knowledgeable instructor, also teaches classes in other old processes, such as wet-plate collodion. I highly recommend both RayKo and Michael.

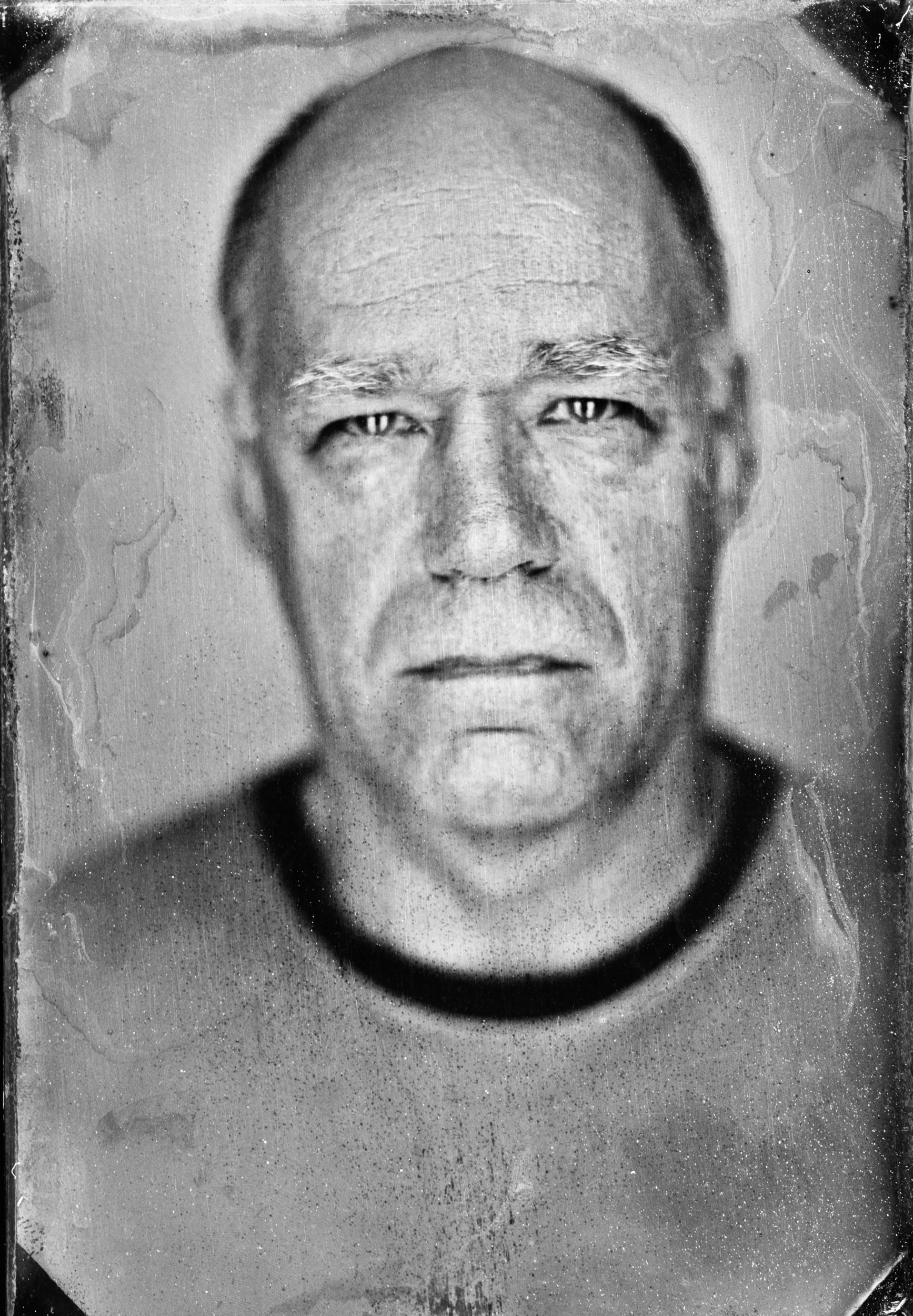

One of the first of the photographic processes, it was perfected by Louis Daguerre (and Joseph Nicéophore Niépce) and introduced to the world in 1839. It is a direct-positive process that creates a singular image on a polished, silver plate. Delicate and ghostlike, the image is unlike any other kind of photograph. The process is laborious and uses hazardous materials. Yet, if one wants to experience the alchemy of photography in a profound and intimate way, it is like nothing else I'd ever seen and I've been intimately involved with photography for almost 40 years.

A copper plate is polished and silver-plated. It is then polished again to a mirror finish. The plate is then sensitized by exposing it to iodine and bromine vapors under safelight. The plate, now sensitive to light, is loaded in a film holder and placed in the back of a view camera. The exposure is long and intense, about 8 seconds under intensely-bright blue lights. A clamp holds one's head still during the long exposure. The plate is then developed by placing it over heated mercury. The mercury fumes form a silver-mercury amalgam on the surface of the plate. The shadow areas of the image have a greater amount of the amalgam, the highlight areas are merely the polished silver. The image is fixed in a solution of hyposulphite and treated with heated gold chloride to strengthen the image.

The process is finicky and intensive. When the gossamer-like image first appears in the fuming tank it seems mysterious, other-worldly. One can only imagine the very first time a human beheld a daguerreotype. It has lost none of its wonder and certainly rekindled my deep love of photography.

Today's image is my attempt to show you the finished daguerreotype of myself, made in the class. While it is a nice approximation, it is not really a daguerreotype. The original is like a piece of jewelry; tiny, delicate, and precious. The image is elusive and can only be seen from certain angles and with certain light. But, the reproduction here gives one at least some indication of the imaging process. The blue-sensitivity of daguerreotype is not flattering to human skin and the long exposures tend to make us look grim and severe. Sitting for a daguerreotype is nothing at all like a snapshot taken with a mobile phone. That is what I loved most about it.